Legislation like the Shrinkflation Prevention Act and Price Gouging Prevention Act would protect consumers by clamping down on corporate greed and deceptive pricing.

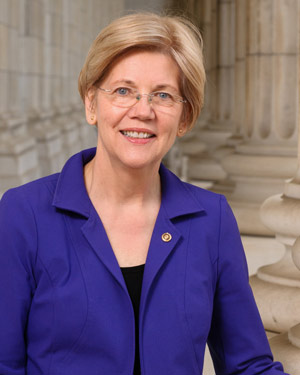

May 4, 2024 - Washington, D.C. — At a hearing this week of the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, & Urban Affairs, U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) questioned Mr. Bilal  Baydoun, Director of Policy & Research for Groundwork Collaborative, and Dr. Alí R. Bustamante, Director of the Worker Power and Economic Security Program for the Roosevelt Institute, on the impact of unfair corporate pricing practices in the food sector on costs, product quality, and the well-being of American families. The hearing follows the introduction of the Shrinkflation Prevention Act, which Senator Warren cosponsored, that would protect consumers by allowing the government to regulate shrinkflation as an unfair, deceptive practice.

Baydoun, Director of Policy & Research for Groundwork Collaborative, and Dr. Alí R. Bustamante, Director of the Worker Power and Economic Security Program for the Roosevelt Institute, on the impact of unfair corporate pricing practices in the food sector on costs, product quality, and the well-being of American families. The hearing follows the introduction of the Shrinkflation Prevention Act, which Senator Warren cosponsored, that would protect consumers by allowing the government to regulate shrinkflation as an unfair, deceptive practice.

Dr. Bustamante confirmed to Senator Warren that over the last 40 years, production costs in the grocery sector have gone down, but corporations have not passed those savings onto consumers. Instead, firms padded their profits by pricing their products above what production costs would call for — ripping off hardworking families in the process. As a result, corporate profits have soared.

Mr. Baydoun, in response to Senator Warren, highlighted tactics like “skimpflation,” dynamic-pricing, and junk fees that companies use — in addition to shrinkflation — to increase profits as much as possible. Senator Warren concluded by calling out big credit card companies who use late fees and high interest rates to drain consumers even more, and called on Congress to pass the Shrinkflation Prevention Act and her Price Gouging Prevention Act to crack down on unfair pricing practices, stop corporate exploitation, and give families needed relief.

Transcript: Higher Prices: How Shrinkflation and Technology Impact Consumers’ Finances

U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, & Urban Affairs

Thursday, May 2, 2024

Senator Warren: Thank you, very much, Mr. Chairman.

If we're going to talk about markets and how perfect markets are, maybe the one thing we should talk about is how concentrated markets have become. And when we have concentrated markets, we have a whole lot less competition.

So, just a handful of companies have taken over the food industry. Thanks to literally hundreds of mergers over the last 50 years, just four grocery chains control an average of 72% of sales in American cities. And in most grocery categories — like bread, pasta, beef, cereal — just four companies control more than 60% of the market.

Now, less competition means food brands don't have to compete on either price or product quality. For families pocketbooks, that means higher prices.

Grocery prices have climbed faster than inflation over the past few years. Now, families are paying 25% more than they did before the pandemic.

So, I want to talk today about the tricks and traps that families face when they head to the grocery store.

Mr. Bustamante, you have researched corporate pricing practices. I understand that when inflation increases, food producers and grocery stores may need to pass on some of those higher costs to customers. But the question is, have groceries gotten more expensive just because of inflation, that is passing along higher prices, or is there more going on here?

Dr. Alí R. Bustamante, Director of the Worker Power and Economic Security Program for the Roosevelt Institute: Thank you, Senator.

What we actually see is that if you look at the long term price, the actual marginal costs of production for many groceries have actually gone down. And part of the big reason for this is actually with just the nature of the supply chains that have actually been developed over time.

That being said, those lower marginal costs were not passed on to consumers. Instead, what we see is that for the past 40 years, this just growing and fascinating trajectory of markups, basically, again, firms pricing their products and services at a much higher rate than the actual increase in costs. And what we see in the past few years, that's just been accelerated due to the pandemic.

Senator Warren: And something they can do because there's a lot of concentration in the industry, so there's not much competition.

In fact, corporate profits rose five times faster than inflation between 2020 and 2022. Kraft-Heinz, which sells everything from Oreos to pasta sauce to coffee, increased profits by 448% over 2022,. Cal-Maine, the largest egg producer in the U.S., increased profits by 718%. In fact, for most of 2023, corporate profits drove over half of inflation.

Now, that hasn't stopped Big Food from pulling out another trick: Jacking up prices was not enough. So, food companies have decided to quietly shrink the size of products, lobbing off a few inches here, a few chips there, a few cookies somewhere else.

This “shrinkflation” is all about deceiving customers so that corporations can pad their profits. The CEO of the snack company Utz admitted, calling shrinkflation, “the path to higher margins.”

So, it seems like we've lost the basic principle of knowing how much something costs before we pay for it.

Mr. Baydoun, you have been studying corporate behavior for years. Have you seen, in your research, have you seen a shift in behavior here?

Mr. Bilal Baydoun, Director of Policy & Research for Groundwork Collaborative: I have, Senator.

Companies deploy a vast array of tactics that really threaten to make the price tag, as we know it, totally obsolete. I'll just name a few. In addition to ‘shrinkflation’ there's also ‘skimpflation.’ This is the idea of degrading the quality of a product by using inferior ingredients, while keeping the price the same or higher. There's also dynamic pricing. This involves changing the price of a product hundreds, thousands, even millions of times in a day or week, making it difficult to predict costs. And finally, there's a practice known as ‘drip-pricing.’ This involves adding on mysterious, confusing fees as consumers are making a purchase as opposed to building all of those fees into the upfront cost.

Senator Warren: Okay, so you got a lot of tricks and traps you identify.

I understand it not only happens when you pull something off the shelf. It also happens when families get to the cash register, when they get ready to check out.

Mr. Baydoun, let's say you've picked out all of your groceries, cashier rings them up or you ring them up yourself, and you use your credit card to pay. Can you talk to us a little bit about the opportunities that big credit card companies have to squeeze consumers on their groceries?

Mr. Baydoun: Absolutely, Senator.

In many ways, customers get gouged once at the checkout line and in many ways they get gouged again if they carry that balance on a credit card, not only through exorbitant APRs, but also through junk fees, like late fees.

You know, up until recently, credit card issuers could charge as high as $41 for missing a payment. But, thankfully, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau actually capped those fees at $8. And that's something that will save 45 million Americans an average of $220 a year, $15 billion annually in total. And so those are the sorts of sorts of interventions we need.

Senator Warren: And special thanks to the Biden administration that has really started attacking these junk fees.

Congress also needs to step up. We need to pass Senator Casey's Shrinkflation Prevention Act to end shrinkflation and my Price Gouging Prevention Act to give the FTC the tools it needs.

Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

Source: Senator Elizabeth Warren