February 9, 2018 - By Emily Becker - Many thanks to Tom for covering my post last month, allowing me to focus on the American Meteorological Society’s annual meeting (where I talked about the blog, and enjoyed my company on the plane ride home). It’s good to be back, and I’m glad to see our La Niña is still hanging around… although probably not for much longer. In fact, the current ENSO forecast from the Climate Prediction Center and IRI predicts a 55% chance that neutral conditions will be in place by spring 2018. Let’s get to it!

Sea shanties

During January, the sea surface temperature in the Niño3.4 region of the tropical Pacific—our primary measurement for ENSO’s ocean component—was close to 1.0°C cooler than the long-term average. This places it comfortably in La Niña territory.

The November–January temperature in the Niño3.4 region was also 1.0°C cooler than the long-term average. Our double-dip La Niña’s second year has been stronger than the first, as the greatest departure from average during 2016–17 was -0.7°C. As Nat showed in his excellent post last week, this is somewhat unusual for a double-dip La Niña, as the second year tends to be a bit weaker than the first. However, as he discussed, the impacts on North American temperature and precipitation tend to be stronger in La Niña’s second year… if you haven’t read Nat’s post, go do it now! I’ll wait.

Carrying the tune

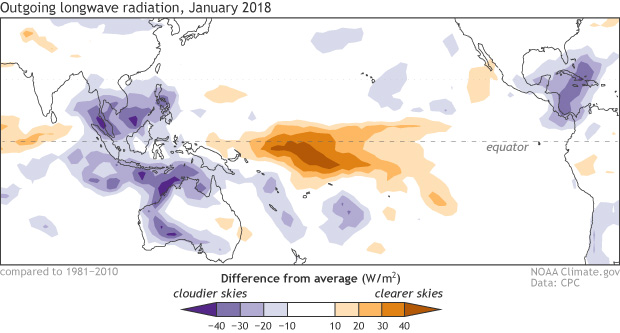

The atmosphere continues to respond to the cooler-than-average surface waters in the tropical Pacific, showing all the signs of a strengthened Walker Circulation. Those cooler-than-average waters lead to less rising air and cloud formation in the central Pacific than average, with more rising air and storms forming over the far western Pacific and Indonesia.

Places that were more (purple) or less (orange) cloudy than the 1981-2010 average during January 2018, based on satellite observations of outgoing longwave radiation (heat). Thick clouds block heat from radiating out to space, so less radiation equals more clouds, and more radiation equals clearer skies. Climate.gov map from CPC OLR data.

More evidence of the strengthened Walker Circulation during January was provided by stronger-than-average near-surface winds (the trade winds), as well as stronger west-to-east winds in the upper atmosphere. The stronger trade winds help to keep the surface cooler, and to keep warmer water piled up in the far western Pacific—part of the critical feedback processes that make up ENSO. However, this feedback doesn’t go on forever, and we’re seeing signs that La Niña’s swan song is imminent.

Bass notes

We keep track of what’s going on under the surface of the tropical Pacific, too, as significant temperature changes in the subsurface waters can provide a valuable clue about the evolution of ENSO events. From early December to late January, an area of warmer-than-average water centered between about 50 and 200 meters (~160–650 feet) under the surface traveled from the western Pacific to the east-central Pacific. This downwelling Kelvin wave chased away most of the cooler-than-average subsurface waters, leaving La Niña without it’s steady supply of cooler waters.

Departure from average of the surface and subsurface tropical Pacific sea temperature averaged over 5-day periods starting in early January 2018. The vertical axis is depth below the surface (meters) and the horizontal axis is longitude, from the western to eastern tropical Pacific. This cross-section is right along the equator. Climate.gov figure from CPC data.

This movement toward more neutral subsurface temperatures is one of the factors forecasters are looking at as we anticipate the decline of La Niña. Most of the computer models also foresee this transition, and overall forecasters have come to the consensus of a 55% chance that La Niña conditions will dissipate by March–May, as the tropical Pacific transitions to neutral conditions.

World music… or, a little off-key?

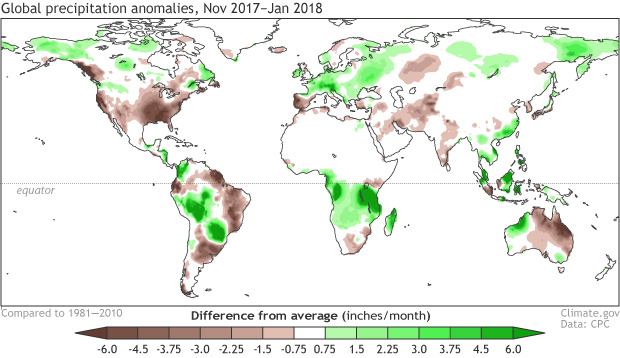

While this La Niña’s effect on precipitation and temperature has been generally in-line with expectations over North America, especially regarding the dry conditions across the southern half of the US, global impacts haven’t been entirely as expected during the past few months.

La Niña during November–January is associated with more rain than average in eastern Australia, northern South America, and southern Africa. On the other hand, La Niña ordinarily tends toward drier conditions in southern Brazil/northern Argentina/Uruguay, as well as southeastern China. (These maps show the expected patterns, but the colors are reversed, since they’re showing El Niño… sorry!) November 2017–January 2018, however, did not conform well to the expected patterns.

November 2017–January 2018 rain and snow patterns, shown as the difference from the long-term mean. Climate.gov figure from CPC data.

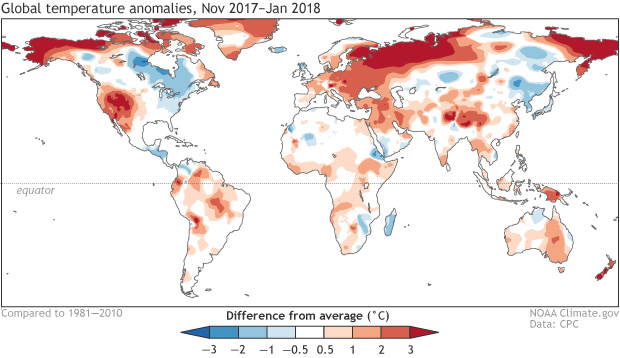

La Niña’s global effects on temperature have historically been associated with cooler temperatures in Australia, southern Africa, and much of South America, but, due to human-caused global warming, it’s increasingly rare to see a lot of cooler-than-average areas over the globe.

November 2017–January 2018 surface temperature patterns, shown as the difference from the long-term mean. Climate.gov figure from CPC data.

This doesn’t mean ENSO is useless as a forecasting tool, but it does further illustrate the complexity of the global climate system, and why forecasts are probabilistic. Over the past few months, La Niña just wasn’t the loudest voice in much of the world’s climate acapella group. (Check out Angel Munoz’s post about La Niña’s effects in South America for a much more effective musical analogy!)

Regarding other voices—stay tuned for Michelle’s later February post on the Madden-Julian Oscillation, who’s been outperforming himself over the past few weeks, likely affecting global weather and climate. Also, the MJO is currently substantially weakening the trade winds, potentially hastening La Niña’s curtain call. Don’t touch that dial! There’s more to come on Radio ENSO, after this message from our sponsors.

A blog about monitoring and forecasting El Niño, La Niña, and its impacts.

Disclaimer:

The ENSO blog is written, edited, and moderated by Michelle L’Heureux (NOAA Climate Prediction Center), Emily Becker and Tom Di Liberto (contractors to CPC), Nat Johnson (NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory), and Rebecca Lindsey (contractor to NOAA Climate Program Office), with periodic guest contributors. Ideas and explanations found in these posts should be attributed to the ENSO blog team, and not to NOAA (the agency) itself.

Source: NOAA