December 20, 2020 - Yale Forestry experts Dr. Mark Ashton and Dr. Joseph Orefice explain the threats to our forests and the solutions we can all be a part of.

What are the characteristics of a healthy forest?

“It is important to first understand that the things that we define as healthy, desirable, or needed from a forest are very much human based,” says Dr. Joseph Orefice, Lecturer and Director of Forest & Agricultural Operations at The Forest School at The Yale School of the Environment.

Mark Ashton, Senior Associate Dean of The Forest School at The Yale School of the Environment; Morris K. Jesup Professor of Silviculture and Forest Ecology and Director of Yale Forests agrees and explains that describing a healthy forest is like describing a healthy human: it’s very complex.

“A forest doesn’t know whether it’s healthy or not, this is a human construct, but from our perspective, the vibrancy and vigor of a forest are indicators of health” Ashton says. “We can attempt to gauge the overarching health of a forest by measuring its growth rate and its capacity to engage in photosynthesis.”

Further, a healthy forest is not necessarily one that is completely untouched; Forests regularly face natural or human-made stresses, and our experts suggest that an important assessment to forest health is its ability to resist and/or adapt to them.

“When thinking about the health of our forests on any scale, it is important to look at resilience and the ability of our forests to regenerate,” Orefice says. “If there is a disturbance, be it a fire, a disease or insect outbreak, or direct human impact, we want to see that the forest can cope with and recover from that disturbance.”

Orefice adds that temperate moist mixed-species forests such as in New England tend to respond well to disturbance and change when there is a diversity in the size, age, and species of trees present across a landscape.

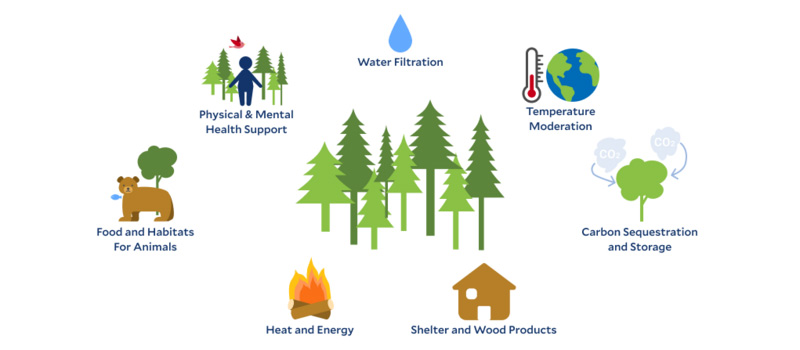

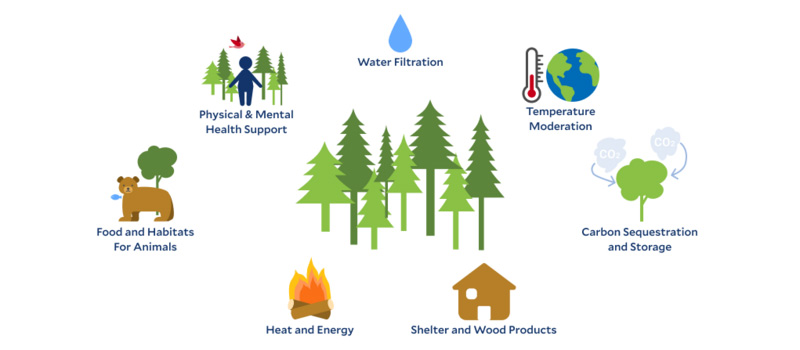

What benefits do forests provide to humans and the environment?

Forests provide humans with a number of benefits including shelter, water, and food. Wood is the basis of construction, flooring and furnishings in many homes, and is extremely valuable to many communities around the world who use primarily wood for shelter. Ashton points out that more than two billion people around the world are also dependent upon fuel wood heating.

In both developed and developing countries, Orefice believes that one of the most important services of forests is their ability to capture and naturally filter our drinking water. Forests can also provide other hydrologic benefits such as flood mitigation and water storage for agricultural irrigation. Many populations around the world use forests as a source of food through wild harvesting, and cultivation, of plants and game.

“In many parts of the world hunting for bushmeat is a very important source of protein,” Ashton adds. “Even for those of us who don’t hunt for survival, there are so many different kinds of medicinal herbs and food crops that we have derived from forests. Cocoa, coffee, tea, and many of our fruits have all been domesticated from our forests.”

Beyond basic survival, forests support human well-being in a variety of ways. By providing recreational opportunities like hiking or birdwatching to offering a pleasant visual pause from the stresses of society, forests present physical and mental health benefits.

Forests play an important role in mitigating climate change. Ashton explains that forests have always served to both evolve with and regulate regional temperature thanks to their ability to absorb radiation and to transpire water back into the atmosphere. Forests also naturally capture and store the carbon that is already in our atmosphere–a key contributor to global climate change–through photosynthesis.

Wood products themselves are an essential material in potentially mitigating climate change because they can both store carbon and serve as renewable alternatives to fossil fuels.

“When we think about our forests and climate, we really need to think about how we can use forests to reduce fossil fuel use,” Orefice says. “Steel, concrete, and plastic are very common building materials, but they’re all incredibly fossil fuel and carbon intensive. Forests, on the other hand, are really our best ability to produce a resource that’s renewable, as wood is the most sustainable substitute to fossil fuel demanding resources in terms of building and construction.”

What are the most pressing threats to our forests today?

While threats differ around the globe, invasive species–or organisms that cause ecological or economic harm in a new environment where it is not native–are the most tangible problem for forests in eastern North America today. Because these species are often accidentally introduced to an ecosystem, for example, through international shipping and horticulture, forests did not evolve alongside these species and are therefore not prepared to live with them. Orefice explains that invasive species of plants might inhibit forests from regenerating, and invasive species of insects or pathogens can knock out entire tree species or reduce certain species ability to grow and thrive.

“We have been incrementally increasing the compounded threats to New England forests due to invasive species,” Ashton adds. “One by one, different species of trees have been taken out of our forests, simplifying their structure, simplifying their tree composition, and therefore simplifying and reducing the ability of forests as a group of organisms to respond to other kinds of potential unforeseen future impacts.”

There are real consequences to this.

“If we lose a tree species, that’s a real challenge in terms of climate change, because we could be relying on it to store a lot of carbon,” Orefice explains. “If a species is lost, its potential climate mitigation benefits are functionally lost from the system.”

Human behavior makes this threat more pronounced. Our fragmentation of forests – meaning breaking it up into parcels for things like suburban development and paved roads – makes forests more susceptible to invasive species and disease. Climate change itself could worsen our ability to predict and react to these threats.

“Climate change could trigger invasive pathogens to act in a certain way ecologically that we are not prepared for,” Orefice adds.

What are the strategies for keeping our forests resilient?

“Many people think that basically leaving the forest alone is the best thing you can do, but as forests get older and older, they potentially become more and more susceptible to insects, diseases, and changes in climate,” Ashton says, explaining that many forested regions have been cleared for agriculture and then with the cessation of such activities, large swaths of single-aged forest have come back.

Much of southern New England is an example of this.

“When you have an even-aged forest that is aging together, for example, it would seem wise to try and break that up by emulating the natural processes of disturbance and regeneration that these trees have already co-evolved with.”

The goal of sustainable forest management is to disturb the forest in an intentional way that leaves the remaining trees with increased resources to grow or to encourage new regeneration. Cutting down trees is not inherently bad when done intentionally and strategically under the guidance of foresters.

In southern New England foresters will often imitate natural disturbances, such as windstorms, by harvesting trees in a way that provides some diversity in the age and height of trees in a forest landscape. Such disturbances create conditions for the establishment and regeneration, and provide residual trees with the increased space they need to grow.

“What we do in forestry is look at forests and say, ‘Which trees do I want to continue to grow? How do I want to manipulate the light and soil conditions in this forest, which is typically done through the cutting of trees, to encourage certain types of regeneration?’,” Orefice says. “Oftentimes, to meet our objectives in terms of forest conditions at the landscape scale, or the local scale, we are doing some type of intentional disturbance to change the ecology of that forest to be more resilient into the future.”

This strategy is something we all do to mitigate our risks each and every day.

“Think about it like investing in the stock market,” Ashton explains. “If you’re trying to mitigate against the vagaries of the market fluctuations going up and down, you invest in all sorts of very different stocks. And not only do you invest in very different stocks, but even within the same kind of stock, you’re trying to invest in different brands and companies. That type of designed diversity is what we’re doing with forest management.”

What can individuals do to help keep forests healthy?

Learning about your local forests is an excellent way to do your part in keeping your local forests healthy. Orefice recommends speaking with your state or private foresters about their strategies for forest management, and how you might also enjoy the various benefits that forests can provide. Ashton suggests that we also take time to learn and incorporate the Indigenous perspective of forests and forest management.

“Indigenous peoples managed these forests fairly intensively through all sorts of ways because it was their source of sustenance, in terms of food, game, and construction,” Ashton says.

Beyond engaging with forests recreationally, Ashton and Orefice suggest learning about the services that forests provide to you each and every day. Research the history of Indigenous lands that you and your nearby forests occupy, and how it has been tended to across periods of history.

“Western society has a very warped perspective of wilderness, where nature is pristine, and humans are divorced from nature, and it’s just not accurate” Ashton says. “If you talk to most Indigenous peoples who work and live in forests, there’s no such thing as wilderness to them. We are very much part of the forest and the forest is very much part of us.”

What Yale is Doing?

Yale has been a leader in forest conservation, science, and education for over a century. The Forest School at The Yale School of the Environment, started in 1900 and served as the foundation upon which Yale became involved in environmental conservation. Faculty at the school have educated forest conservation leaders and advanced forest science for the last 12 decades. Yale currently has 10,880 acres of forestland in Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Vermont dedicated to providing educational, research, and professional opportunities. The Yale Forests, as they are known, are managed by The Forest School but valued and utilized by students and faculty throughout Yale.

The Yale Forests are part of working landscapes and are managed to provide sustainable forest resources while increasing landscape level biodiversity and resilience. Management prescriptions encourage species and structural diversity by creating conditions that both create new age-classes by periodically establishing natural regeneration in certain areas while at the same time insuring the protection of other parts of the forest to become much older.

Implementing these regimes over time slowly converts a single-aged homogenous forest to one that is multiple-aged, structurally complex and higher in plant and animal diversity. We believe that that this approach ensures a forests’ ability to recover from major disturbances such as hurricanes and droughts and to better withstand impacts of introduced insects, diseases and invasive plants and animals. Long term faculty research is focused on monitoring these management activities and gauging forest resilience in different ways. Faculty and research students seek to understand both the theoretical and applied aspects of several important areas of ecology: 1) microbial decomposition and carbon, 2) the dynamics of food webs on both fresh water and terrestrial systems, and 3) the successional dynamics and diversity of forests.

Students are involved with forest management every step of the way. Yale Forest Post-Graduate Fellows, typically recent Master of Forestry graduates, and student forest assistants work directly with faculty to plan and implement forest operations, research, and educational opportunities for Yale and local communities. The highlight of our student engagement is in the summer when Masters students learn the practical aspects of forestry during a 12-week intensive, affectionately known as “Forest Crew”. These students overlap their stay at the Yale Forests with research students and incoming Masters student at The Yale School of the Environment, creating a seasonal forest community with ever evolving exchanges of knowledge, experience, and enjoyment.

Source: Yale