Action needed as California surpasses 500,000 cases, national death exceeds 150,000

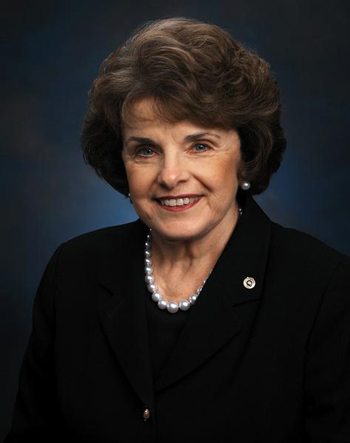

August 5, 2020 - Washington - Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) on Tuesday submitted the following remarks to the Congressional Record laying out the current coronavirus  situation in California and across the country and the need for a national plan to combat it:

situation in California and across the country and the need for a national plan to combat it:

“The first case of COVID-19 was reported in the United States on January 20. In the intervening six months, we’ve seen cases climb, then fall, and now surge once again.

More than 4 million Americans have been infected with coronavirus. So far, more than 155,000 have died. Every day for the last four months I’ve received an update from my staff on coronavirus numbers. I’ve watched, day by day, the number of positive cases climb. In California right now, 30 of our 58 counties have had more than 1,000 positive cases.

The numbers just go up and up and up. It becomes impossible to look at the charts and graphs and not come to the conclusion that we have to do more, and maybe significantly more.

Simply put, this is the worst pandemic in my lifetime. You have to go back more than 100 years to the Spanish flu epidemic to find something comparable.

But the unprecedented scale of this crisis is no excuse for our failure to respond more forcefully and in a nationally coordinated manner.

Once we realized the scale of the outbreak in the spring – both by the increased cases at home as well as monitoring stricken countries like Italy – it became clear that we needed strong leadership from the top.

We didn’t get that.

Instead, the White House and President Trump blamed states for the lack of testing equipment, the hoarding of sanitizing supplies and the absence of protective gear.

In March, President Trump said, “I don't take responsibility at all.” That’s a direct quote from the president of the United States, in the midst of a global pandemic with body counts rising around the country. We must do better.

More recently, during the renewed surge in cases, we’ve seen a repeat of those problems. We know we need more testing supplies and protective equipment, but rather than implement the Defense Production Act and stock up on supplies, we saw little action from the White House.

I’ve been thinking back to the early days of the pandemic. In March, San Francisco’s Bay Area imposed the first significant stay-at-home order in the country. California soon followed.

It was criticized at the time as an over-reaction, but it succeeded in slowing the rate of spread and the death toll remained lower than many other large states. Soon, much of the country had similar orders in place.

In April and early May, there was a sense of shared sacrifice. People stayed at home, schools closed, many lost their jobs. Our way of life shifted in the most abrupt way since at least 9/11, if not World War II.

But the understanding was that we made these sacrifices because they would help control the virus. We would “bend the curve,” we would produce sufficient protective gear, and we would make it safe for people to return to their lives.

The idea was that, by the end of summer, life would return – if not back to normal, at least back to some version of it.

It’s now almost August. The number of new cases climbs each day. K-12 schools have announced they will be closed in the fall. Many colleges are following suit. Job losses continue with more than 30 million still receiving unemployment benefits.

Simply put, America failed the test of re-opening.

If we had responded like other countries – with comprehensive national policies for mask use, avoiding crowds and increasing testing capacity – we could have been returning to normal life right now.

Instead, many cities and states are rolling back their re-opening plans and may have to re-institute stay-at-home orders to get the nation back to where we were before Memorial Day.

President Trump last week said the administration is “in the process of developing a strategy” to fight coronavirus.

At some point we’ll want to know why it took seven months for him to acknowledge a national plan was necessary. Right now, however, we need to focus on what that plan will entail.

Just as importantly, we need to focus on who should have input into the tenets of such a plan. In a word: “Experts.”

This is a challenge that requires the combined minds of our best and brightest, particularly public health and infectious disease experts. This is not an arena for politics. Period.

So what do those public health experts propose? After reading material and listening to a range of opinions, there are five areas that appear to have broad consensus:

First, we need to ensure that masks are used everywhere.

Early on, we knew simple acts like talking and even breathing caused airborne transmission of the virus, especially in confined areas like office buildings. We also knew individuals who weren’t showing symptoms could spread the virus to others because symptoms don’t appear for five to seven days. And research continues to show masks are one of the best tools to slow the spread of the virus. Scientific modeling is clear: masks prevent the spread of the virus.

Yet even with this knowledge, we still continue to see a patchwork of policies around the country.

A national mask mandate would dramatically reduce the spread of the virus, especially by those who don’t yet show symptoms.

On July 14 the CDC called on all Americans to wear masks. CDC Director Robert Redfield said if all Americans wore masks, the current surge in cases could be brought under control within two months.

Masks work. We need a national mask mandate.

The second step is a national program for testing.

Months into this pandemic, we continue to hear stories of people not able to receive a test. In some cases my office has heard from people with fevers and coughing but are still told to stay home and not get tested.

Simply put, anyone who wants to be tested should be, and the results should be returned within 24 hours, not a week later.

Studies have found that if we only test individuals who show symptoms, it’s too late to stop further transmission.

That means states and cities need sufficient supplies to dramatically increase testing. At this time, that’s not happening. A national testing strategy would help coordinate action and prevent states from having to compete against each other.

The third step, related to increased testing, is ensuring we have enough testing supplies and safety equipment for frontline workers.

The president could quickly implement the Defense Production Act. This law would allow the federal government to address supply chain issues and increase production and distribution of testing supplies, medical equipment and personal protective equipment.

This should have been done months ago, but so far the president has only selectively used this tool. He should broaden its use immediately.

It is unconscionable that six months after this virus appeared on our shores, essential workers around the country still lack personal protective equipment – not only doctors and nurses but grocery clerks, agricultural workers, public transportation operators, educators and many others.

These individuals are putting themselves at risk to provide necessary services to the public and they should have access to masks and other equipment to keep themselves safe.

The fourth step is expanding contact tracing, another area where we see a patchwork of policies across the country rather than a cohesive national effort.

To work, contact tracing must occur immediately after an individual is found to be infected. A team determines everyone with whom an infected individual had recent close contact and encourages them to get tested, self-isolate and monitor their health.

Right now, on average, everyone who gets COVID passes it to more than one other person. In other words, the spread is increasing, often by those who don’t know they’ve been exposed. Contact tracing will help solve that.

The logistics, however, often aren’t feasible for local governments. That’s why a federal contact tracing program – possibly using Peace Corps and AmeriCorps volunteers as has been suggested – is so important.

Finally, the fifth area is the need for a plan to manufacture and distribute a vaccine once it’s developed.

A key component is determining priorities for vaccine distribution. Should it go first to essential workers on the front lines? Or should it go to people most likely to get the virus, the vulnerable populations and those in hard-hit areas? These aren’t easy questions and we should work on answers now.

We also need to handle the logistics involved to ensure rapid distribution of the vaccine nationwide.

These are obvious challenges, but they’re also complex and we need a plan in place now, ahead of vaccine development, rather than waiting until a vaccine is developed.

In addition to those five health-related planks, I also believe we need a coordinated plan to help the small businesses and workers suffering during this time.

One example is the Paycheck Protection Program that helped many small businesses. The program provides forgivable loans if businesses use funds on employee salaries and other necessities to remain afloat, which will allow them to quickly reopen when it’s safe.

Another example is the additional $600 in unemployment benefits in the CARES Act. This assistance allows millions of families to pay rent, cover bills, buy food and contribute to the economic recovery. Unfortunately that vital aid has lapsed.

Since mid-March, more than 60 million Americans have filed for unemployment benefits. Today, more than 30 million people continue to depend on these benefits.

We can’t cut these lifelines until jobs are available for those out of work. If the economy remains shuttered and we do nothing to help families and businesses, we’re telling millions of Americans that we don’t care they’re hurting.

Moreover, we’re hurting our own economic recovery by taking aid from those who most need it, the very people who are most likely to spend it to support the economy.

The federal government exists for a reason, and that’s to help Americans do things they can’t do for themselves. The same goes for states, which are responsible and powerful but can’t do it on their own.

A global pandemic calls for a robust federal response, which must entail a national response plan. And that plan has to be based on science and on data, not politics.”

Source: Senator Dianne Feinstein