August 27, 2025 - By Ching Lee - As a cow-calf producer, Calaveras County rancher Michael David Fischer is bucking a national trend that has kept the U.S. cattle supply tight and the price of beef at near-record profit levels.

While other cattle ranchers are selling their animals while the market is red-hot, he’s holding on to more heifers for breeding, so he can rebuild his herd after California’s multiyear drought several years ago forced him to reduce his numbers.

“I saved more replacements than I have in the past because I’m trying to get back to where I was,” David Fischer said. “I’ve got to look ahead and not take the big check this year.”

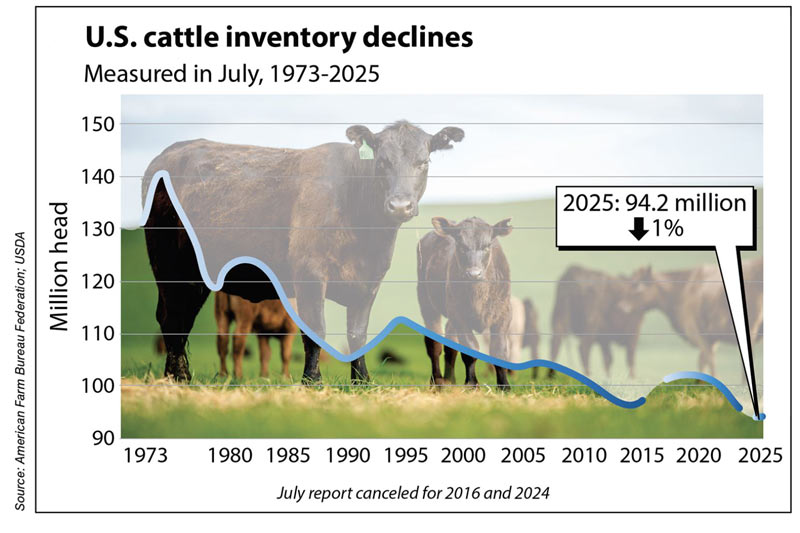

Despite some ranchers trying to grow their herds, the nation’s cattle inventory—totaling 94.2 million head as of July 1—remains historically low and continues to shrink, according to the latest estimates by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Drought conditions may have eased in large parts of California in recent years, allowing ranchers such as David Fischer to start rebuilding, but persistent drought in other major beef-producing states has decimated the nation’s overall cattle population.

With cattle prices remaining so high, ranchers are more inclined to sell calves for cash rather than retain them for breeding, said Abbi Prins, an industry analyst for CoBank in Minnesota. Drought and poor pasture conditions in parts of the country during the past couple years also have made it harder for ranchers to keep more breeding stock and feed their cattle.

After drought annihilated ranchers’ bottom lines, David Fischer said many cow-calf operators are “finally getting out of the red a little bit,” and with current cattle prices “going absolutely crazy, it encourages them to sell.”

“It’s very hard to look at the prices and say, ‘I’m going to keep this heifer when she brings $2,500 as a young heifer,’” he said, especially if they think the price may go down next year.

Even though he’s trying to expand his herd, David Fischer said he’s doing it slowly by keeping more heifers rather than buying cattle. By raising his own, it will take him several years to rebuild, he said. Other ranchers he knows are selling rather than retaining heifers while prices are up as they try to pay off their debts, he noted.

CoBank’s Prins said she expects the size of the nation’s beef cowherd won’t start to see signs of expansion until 2027 because it takes nearly two years for heifer calves born this year to produce their own calves.

While USDA’s latest cattle numbers do not show “further decline on an exponential level,” she said, “we aren’t necessarily seeing rebuilding yet either.” There are “pockets of rebuilding,” she noted, “but they are too small to shift the national number just yet.”

Beyond 2027, Prins said she does not anticipate an immediate “massive bump” in new beef-cow inventory, but it could be enough to show a positive change.

Bernt Nelson, an economist at the American Farm Bureau Federation, has called the current expansion and contraction in the U.S. cattle herd a “hypercycle,” as the industry is in its 12th year of the cycle and its seventh year of contraction. Most cycles last about 10 years, he noted, “but this is not your typical cattle cycle.”

For ranchers nearing retirement, selling cattle while prices are strong is attractive compared to borrowing money at high interest rates to buy cattle. At the same time, high cattle prices and the high cost of borrowing money prevent newcomers from growing their business, Nelson said in his analysis of the USDA July cattle inventory report.

“It’s a good time to get out and a hard time to get in—a big reason the ‘hypercycle’ continues,” he wrote.

Despite a decent hay crop thanks to good rains this year, Tulare County rancher Chris Lange said his operation is not in expansion mode. He sold heifers in recent months that were originally identified as replacements “just because the price was so good.”

“We’re being a little bit cautious, but we are definitely selling off animals—young steers and young heifers in particular,” he said. “We’ve been very satisfied with the financial returns on all of them.”

Lange said he’s heard “doomsayers” warn that the current robust market won’t last forever, as consumers will stop eating beef if prices become too high. But so far, demand “seems to be as strong as ever,” he said.

Indeed, resilient demand for beef has kept prices at unprecedented, elevated levels, with USDA forecasting a rise in cattle prices for the rest of the year and higher prices into 2026, according to the department’s World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates report this month.

At the same time, beef imports, particularly from Brazil, have dropped due to higher tariff rates, further tightening domestic supplies, USDA reported.

Gaylor Wright of California Fats and Feeders, a cattle seller and buyer in Oakdale, said he is concerned that beef prices have gotten too high, with fears that shoppers may soon turn to other proteins such as pork or chicken.

“I don’t know how it can get any better,” he said, referring to the cattle market. “We can sell all the product that we produce, and everybody’s making good money. We don’t need to have prices get any higher.”

Another factor that could further complicate U.S. cattle supplies is the New World screwworm, a parasitic fly that burrows into the flesh of living mammals, eating them alive. The pest has been found in Mexico, prompting the U.S. in May to temporarily close its southern border to Mexican cattle, bison and horses to protect domestic livestock. Though a phased reopening of some ports of entry was in the works, new discoveries of the fly in Mexico nixed those plans.

Feeder cattle from Mexico accounts for about 5% of the U.S. feeder cattle supply, Prins of CoBank noted. While that number may not seem significant, she said, “it does matter.” She said the U.S. has been importing more lean beef from Australia, Brazil and Canada because of low dairy cow and beef cow slaughter. The imported beef is then mixed with more fatty U.S. beef to make ground beef.

Cattle broker Wright said feedlots are feeding cattle longer, and packers now want bigger carcasses “because they’re able to sell every pound that they can produce and get their hands on.” With U.S. cattle and calves on feed the lowest since 2017, bigger carcasses—which used to be undesirable and discounted—are helping to offset tight supplies, he said.

“They want that tonnage,” he said. “They want that big carcass just to create more meat because there is such a shortage.”

Ching Lee is editor of Ag Alert. She can be reached at clee@cfbf.com.

The California Farm Bureau Federation works to protect family farms and ranches on behalf of nearly 32,000 members statewide and as part of a nationwide network of more than 5.5 million Farm Bureau members.

Reprinted with permission CFBF